MONOGRAPHS

A Place by the Sea: Excavations at Sewerby Cottage Farm, Bridlington

By Chris Fenton-Thomas

Excavations in 2000 revealed a sequence of middle to late Neolithic occupation consisting of at least three Neolithic buildings, which at the time of discovery, was the highest concentration of such structures to have been found in the north of England. Around the middle of the 4th millennium BC a series of small-scale structures were erected within a natural hollow. The abandoned remains were overlain by deposits bearing several thousand pieces of flintworking waste. A post-built structure was constructed during the late Neolithic further along the same hollow. Further Neolithic occupation was identified in another hollow in separate excavations in the farmyard during 2003. Five groups of pits, spanning the middle to late Neolithic, many of which contained deposits rich in pottery and flint waste were revealed.

It is rare to find evidence for Neolithic occupation and buildings but exceptional to discover a site where the Neolithic archaeology is stratified showing repeated visits to the same place over such a long period of time.

During the late Iron Age much of the development area was enclosed by land boundaries, a square barrow and round barrow were also constructed at this time. The square barrow contained a late Iron Age inhumation and was furnished with an iron dagger and missile head. A rural farming settlement built up around the land boundaries and barrows and occupation continued until the end of the 2nd century or middle of the 3rd century AD. The settlement was based around arable cultivation and livestock. Three crop-driers were used between the 1st and 2nd centuries AD and in the north of the site there was evidence for a system of fence-lines and droveways related to livestock management.

This farmstead was abandoned by the middle of the 3rd century but there is evidence for some occupation during the Anglian and mid-Saxon periods. Finds of Ipswich ware indicate some activity during the 8th or 9th century AD. This kind of pottery is only rarely found in East Yorkshire.

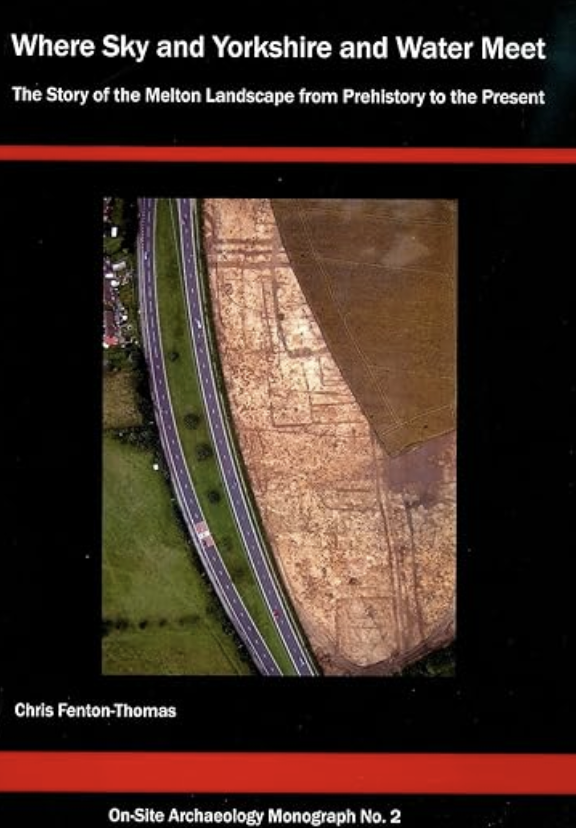

Where Sky and Yorkshire and Water Meet: The Story of the Melton Landscape from Prehistory to the Present

By Chris Fenton-Thomas

A multi-period prehistoric, Romano-British and medieval landscape, complete with land boundaries, trackways, burials and occupation areas were revealed during excavations in 2004-2005. There was an almost continuous sequence between the third millennium BC and the eighteenth century AD. The earliest features consisted of a group of early Bronze Age pits, a round barrow, which later formed a focus for cremations, inhumations and land boundaries. The site was crossed by major north-south land boundaries of late prehistoric date as well as a ditched trackway that ran east to west. Both these linear features were probably constructed around the beginning of the first millennium BC. A group of early Iron Age burials had been placed alongside the north-south boundary on its eastern side and they may have formed part of a linear cemetery. A late Iron Age settlement was revealed to the north of the trackway including roundhouses, pits, burials and other structures.

A square barrow of late Iron Age date was found close to the earlier round barrow. The settlement was abandoned or moved before the Roman Conquest but the trackway remained in use for many centuries. Many of the ditches that formed the boundaries of smaller enclosures across the site were dug during the Roman period. Although there was little evidence for Roman period structures the site was used for agricultural purposes until around the middle of the third century AD. A crop drier was constructed in a partially filled Roman ditch and it was given an archaeomagnetic date of between 200 and 250 AD.

Excavations also uncovered rare and unexpected evidence of Anglo-Saxon occupation from the sixth or seventh century AD. This was contemporary with a group of four inhumations that were placed in the junction of the two trackways identified north of the road, suggesting that they were still in use at this time. After this period, there were few signs of activity until the twelfth century AD where evidence of occupation on the southeastern side of Melton village was identified. During the medieval period, the rest of the site appears to have been part of the arable field systems except for a small number of scattered pits or sunken-featured buildings.

The Romans at Nostell Priory: Excavations at the new visitor car park in 2009

By Dave Pinnock

During excavations in 2009 five phases of archaeological activity were identified. Iron Age activity consisted of a small number of shallow ditches indicative of land division and an enigmatic, massive ditch that was backfilled and later re-cut in the early Roman period.

The earliest Roman phase was dated by Flavian-Trajanic pottery of types associated solely with Roman military sites. In addition, the presence of wasters indicated the operation of a previously unknown nearby kiln producing both fineware and mortaria. Evidence for land divisions, for water management in the form of a robbed-out stone-lined well and two clay-lined lined cisterns, and an oven of uncertain function were also identified. A rectangular arrangement of postholes may have indicated the presence of a building extending beyond the edge of excavation. Additional support for the military nature of this phase comes from other material culture found in unphased contexts including bessales and a box-flue tile that probably originated in a hypocaust and a quern of twin hopper design that is usually associated with military establishments. It seems likely that the remains represent a vicus adjacent to an, as yet, unidentified Roman fort.

Three further phases at the site characterised by land divisions, pits and an unusual double-flued crop drier were also identified, dating from the mid second to the late third or fourth century. Unlike the early Roman phase, the pottery from these phases lacked military associations and was of types familiar from rural settlement elsewhere in the region. So radical was the break from the earlier pottery types that there may even have been a hiatus in the habitation of the site after the early Roman phase.

Several undated features were present, the most significant of which was a group of burials, including a stone-lined grave, located towards the eastern limits of the main excavated area. A complete absence of bone (animal or human) surviving in any of the features on the site hindered interpretation, so it is not clear whether these were originally full burials or ‘empty’ graves occasionally found elsewhere. Near the graves an undated 3m diameter unbroken ring ditch has been identified as a possible shrine.